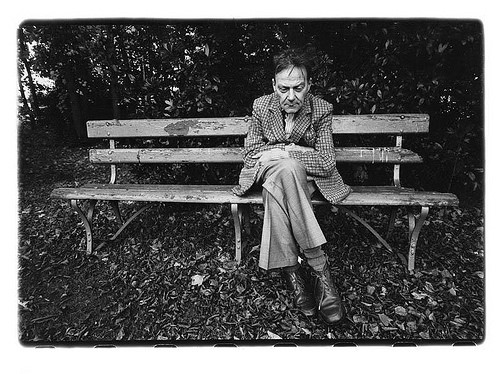

I first came across the poetry of Ivan Blatný (1919 – 1990) several years ago, and was immediately struck by the remarkable circumstances of his life. One of the leading Czech poets of his generation, he defected to England in 1948, becoming a non-person in his own country – all references to him were expunged, and his poetry was black-listed. Life in exile was not easy for Blatný – he suffered a mental breakdown soon after his arrival, but recovered sufficiently to work for a time as a journalist for the BBC and Radio Free Europe. From 1954 until shortly before his death he lived in mental institutions and care homes in Essex and Suffolk, spending the last 5 years of his life in a nursing home in Clacton-on-Sea. He was not so much mentally ill as paranoid about being kidnapped and returned to Czechoslovakia. For about 10 years he stopped writing, but then began to fill dozens of notebooks, most of which were simply thrown away by his carers. In 1977 a nurse discovered his identity and began preserving his work: a collection of his writing eventually found its way to Prague, where it was published in samizdat in 1982. His poetry began to be published openly in Czechoslovakia in the year of his death.

I have set, for baritone and an ensemble of 12 players, poems from the 1940s in translation as well as some of his later poetry, much of it composed in English as well as in a polyglot mixture of English, Czech and German. The title, ‘As time returns’, is taken from a line from a poem in the collection ‘Old Addresses’, published in Canada in 1979.

‘To go here and there, slow to return,

as time returns, as distance returns too,

nostalgic like stamps on a letter.’

(translated by Matthew Sweeney)

Commissioned by the Koussevitzky Foundation, Library of Congress, and the London Sinfonietta for first performance in the Purcell Room, Southbank Centre, on 7 December 2018 by George Humphreys and the London Sinfonietta conducted by Jessica Cottis.

Translations are indicated by italicised text; all else is Blatný’s original

- Black

Come on you lazy censors

confiscate my poem

put a dark oblong in its place

(I wanted to say black –

black jako na úmrtním oznámení

(black as in the obituary)

– from Afterword

- Ba, Ba, Black Sheep

The mountain black sheep descended

to the valley but Rosa Bonheur

can’t paint them black is

the colour of death and there is

no death in the universe

Luckily enough because I enjoy life

pendling between the table and the television

Be quiet sister

a monad can die

I’ll stay a bit selfishly

thinking only of the coloured cover

of the book on the table in my workshop

– from Uncollected Poems (1980s)

- Autumn

Raking leaves in the park, what could be better.

To go here and there, slow to return,

as time returns, as distance returns too,

nostalgic like stamps on a letter.

I found a letter, written only in lead,

rainworn, half torn.

O epistolary era, where have you fled?

I have written long letters as Rilke used to;

no more, farewell, it’s November, late.

The red horses are out of the gate.

– from Old Addresses (1979)

translated by Matthew Sweeney

- The drifter sleeps in the meadow

The good for nothing wanders the city streets

always under pressure of the moral institutes

But he won’t go to a borstal

meadows die Wiesen await him outside of the city

Wie dream as dream how a dream

zbytečná otázka

(a useless question)

no matter I can’t remember a thing.

– from Bixley Remedial School (1979, 1982)

translated by Veronika Tuckerová and Anna Moschovakis

- Small Variation

Thursday 8p.m. On the table:

Matches, cigarettes, tobacco, knife, and lamp.

My tools.

You already know my music from five or six things,

You already know my music from five or six things,

My little song,

As it sizzles on the stove, as it bubbles in quietude,

The song of the interlude, Which happens only once in history.

Matches, cigarettes, tobacco, knife, and lamp.

And dust on all of them.

The silent horse gallops and carries it on hoof.

Dust of the barren flat.

Dust of the barren flat.

For the last time unsettled, is lost into history.

– from This Night (1944)

translated by Matthew Sweeney

- The life of bees

Queen, drones, bee-workers, život včel*

that is the bee-hive’s personnelle

Now I must whisper in low tone

I was today a dying drone

But I am fresh and Glück-alive

back in the úl, back in the hive

– from Another Poetical Lesson (1980s)

* ‘the life of bees’, a reference to Maeterlinck’s ‘La vie des abeilles’; ‘úl’ is ‘hive’. This is the only late polyglot poem with a rhyme scheme.

- Interlude 1

- Autumn III

All my lovely years, where have they whirled,

those lovely hallways that led to sweet women,

the murmurs, ankles, the magic of the world?

Oh why, why did I stay alone, alone, alone?

The orchard shook and fell like a dead goddess.

The undertakers usher out the bier.

The castle stands, oh nonetheless,

and shreds fly far and near.

The villages drowse in the autumn plains

while actors take their grease paint off the train

The curtain rises. The band begins to play.

– from Old Addresses

translated by Justin Quinn

- Interlude 2

- If you came with me

If you came with me, you’d see what I like.

A church, a bridge, a ditch – this country side

so ordinary and beautiful beside

a river, the chestnut’s fragrant shade, its look

So water from the well clears off the dust

that settled on a face ruddy and tanned,

and falls on books, on a letter from a friend,

and covers paintings quietly drapes a bust.

It was July and I was coming back.

You at the window, waving from afar,

the swifts just risen like an airborne bazaar,

glittering roosters, the castle’s glossy stack.

And near the earth the sky was set ablaze

by wooded hills, then darkened from the top.

I heard a cry above the goldsmith’s shop.

For breakfast I had strawberries. Such days!

– from Brno Elegies (1941)

translated by Justin Quinn

- The Last Poem / Fate

I have now two pens and plenty of papers

The will to life is remorselessly exploding all eternity

there is no death (luckily enough)

we must acquiesce

there is now and then the yes

yes we want it so

we can’t choose the absolute nothing.

– from Bixley Remedial School